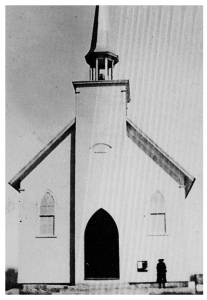

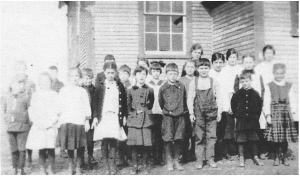

Historic sites are valuable parts of our heritage. They represent tangible and direct links to our past and, as such, need to be recognised and cared for by our society. Churches, cemeteries, schoolhouses, barns, farmhouses and mills are eloquent testimony to religious beliefs, education, farming practices, social organisation and of the values held by the inhabitants at different times. These historic landmarks are often endangered by developers, gravel pits, vandals, lack of funds and general neglect; and always by the passage of time.

This is why we have created a page on the West Bolton website, to alert residents and visitors of the existence and value of these signposts to our past. Contributors to this page include: Thor Arnason, Robert Chartier, Nancy Dixon, John Fowles, Kathy LePoer, Arthur Mizener and Heather Tuer. We form a sub-committee of the Cemetery Committee of the Missisquoi Historical Society.